• Daniel Baker

Posted in Grace

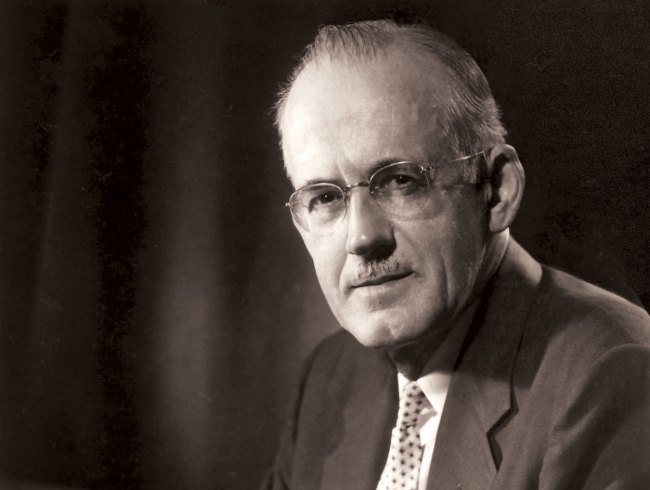

For years, A.W. Tozer wrote an editorial for his denominational publication, Alliance Life Magazine. Eventually another of its editors, Anita M. Bailer, captured some of these for a book called, That Incredible Christian. One of these reflections was on "The Futility of Regret." It contains numerous insights on heretical and Pharisaic tendencies—and the grace to escape these. Below is his reflection with just some section headings added.

******************

We're all recovering heretics and legalists

The human heart is heretical by nature. Popular religious beliefs should be checked carefully against the Word of God, for they are almost certain to be wrong. Legalism, for instance, is natural to the human heart. Grace in its true New Testament meaning is foreign to human reason, not because it is contrary to reason but because it lies beyond it. The doctrine of grace had to be revealed; it could not have been discovered.

The essence of legalism is self-atonement. The seeker tries to make himself acceptable to God by some act of restitution, or by self-punishment or the feeling of regret. The desire to be pleasing to God is commendable certainly, but the effort to please God by self-effort is not, for it assumes that sin once done may be undone, an assumption wholly false. Long after we have learned from the Scriptures that we cannot by fasting, or the wearing of a hair shirt or the making of many prayers, atone for the sins of the soul, we still tend by a kind of pernicious natural heresy to feel that we can please God and purify our souls by the penance of perpetual regret.

Godly sorrow is different than futile regret

This latter is the Protestant’s unacknowledged penance. Though he claims to believe in the doctrine of justification by faith he still secretly feels that what he calls “godly sorrow” will make him dear to God. Though he may know better he is caught in the web of a wrong religious feeling and betrayed.

There is indeed a godly sorrow that worketh repentance, and it must be acknowledged that among us Christians this feeling is often not present in sufficient strength to work real repentance; but the persistence of this sorrow till it becomes chronic regret is neither right nor good. Regret is a kind of frustrated repentance that has not been quite consummated. Once the soul has turned from all sin and committed itself wholly to God there is no place for regret. When moral innocence has been restored by the forgiving love of God the guilt may be remembered, but the sting is gone from the memory. The forgiven man knows that he has sinned, but he no longer feels it.

The effort to be forgiven by works is one that can never be completed because no one knows or can know how much is enough to cancel out the offense; so the seeker must go on year after year paying on his moral debt, here a little, there a little, knowing that he sometimes adds to his bill much more than he pays. The task of keeping books on such a transaction can never end, and the seeker can only hope that when the last entry is made he may be ahead and the account fully paid. This is quite the popular belief, this forgiveness by self-effort, but it is a natural heresy and can at last only betray those who depend upon it.

Joy and peace are appropriate for the Christian—even though sin remains

It may be argued that the absence of regret indicates a low and inadequate view of sin, but the exact opposite is true. Sin is so frightful, so destructive to the soul that no human thought or act can in any degree diminish its lethal effects. Only God can heart that has been delivered from this dread enemy feels not regret but wondrous relief and unceasing gratitude. The returned prodigal honors his father more by rejoicing than by repining. Had the young man in the story had less faith in his father he might have mourned in a corner instead of joining in the festivities. His confidence in the lovingkindness of his father gave him the courage to forget his checkered past.

Regret frets the soul as tension frets the nerves and anxiety the mind. I believe that the chronic unhappiness of most Christians may be attributed to a gnawing uneasiness lest God has not fully forgiven them, or the fear that He expects as the price of in the goodness of God mounts our anxieties will diminish and our moral happiness rise in inverse proportion.

Is it conviction for sin or self-love that we're experiencing?

Regret may be no more than a form of self-love. A man may have such a high regard for himself that any failure to live up to his own image of himself disappoints him deeply. He feels that he has betrayed his better self by his act of wrongdoing, and of face that is not soon forgotten. He becomes permanently angry with himself and tries to punish himself by going to God frequently with petulant self-accusations. This state of mind crystallizes finally into a feeling of chronic regret which appears to be a proof of deep penitence but is actually proof of deep self-love.

Christ-regarding, not self-regarding, is the answer

Regret for a sinful past will remain until we truly believe that for us in Christ that sinful past no longer exists. The man in Christ has only Christ’s past and that is perfect and acceptable to God. In Christ he died, in Christ he rose, and in Christ he is eated within the circle of God’s favored ones. He is no longer angry with himself because he is no longer self-regarding, but Christ-regarding; hence there is no place for regret.

************

It's good to be convicted of sin, but Tozer helps us see the difference between true conviction and a self-regarding and self-atoning and ultimately futile regret.

Daniel